The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of collecting and reporting data on health outcomes by race and ethnicity in order to quantify the way in which the virus’s impacts fall along existing lines of health and structural inequity. Just this past week, the federal government announced that it will require data on race and ethnicity to be collected for all COVID-19 tests.

The push for these data sits within a broader conversation about the importance of collecting racial data that has been ongoing among those working toward health equity and to mitigate the negative impacts of the “social determinants of health” – or the place-based conditions that impact the health of individuals and communities.

Over the last month or so, more and more articles have been published discussing the disparate impact of COVID-19 on African American, Indigenous, and Latinx people. These articles bring to light the ways in which existing inequities – both in terms of access to resources and healthcare, and resulting from historic processes of discrimination such as redlining – are manifesting in COVID-19 infection and mortality rates.

This burgeoning discussion also has brought into clear focus the inconsistencies in how data on race and ethnicity are collected and shared at the state level. Some states have robust data on COVID-19 testing results and death rates that include granular information by race and ethnicity and have made these data easily accessible to the public. Other states are lagging behind.

One of the clear principles among those working to mitigate health disparities is the need to collect and report race and ethnicity data in order to understand differences in health outcomes before we can determine how to intervene in order to mitigate these inequities.

Our lab decided to look into how states have been collecting and sharing data on COVID-19 testing and deaths by race. The COVID Tracking Project recently teamed up with the Antiracist Research & Policy Center to aggregate race data by state and to highlight where the gaps are. (Check out their regularly updated racial data tracker here.)

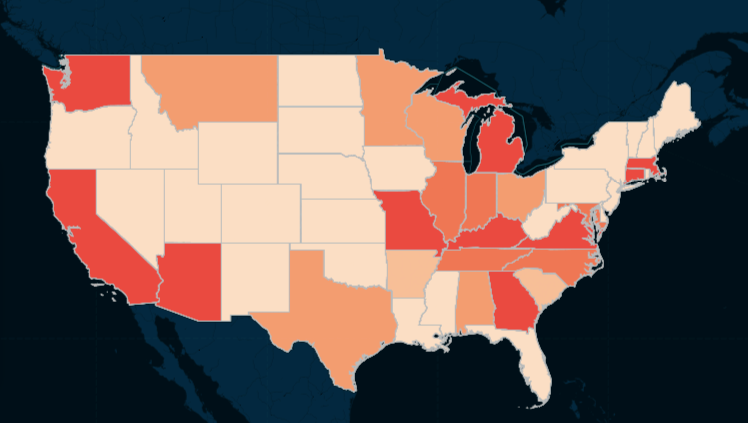

Using their data, we created these maps that show the percent of missing data on race and ethnicity among those who have tested positive for COVID-19, by state. The darker colors indicate states where the race and ethnicity of those who have tested positive for COVID-19 is least known.

(Data pulled June 4, 2020 from https://covidtracking.com/race)

(Data pulled June 4, 2020 from https://covidtracking.com/race)

It’s important to note, though, that even where testing data and outcomes are reported by race and ethnicity, an outstanding question remains of who is and isn’t being tested. Even the most “complete” datasets don’t answer this more fundamental question. Though the federal government’s new requirement is vital to filling gaps in the data, this question of who is and isn’t tested will persist until testing becomes more ubiquitous.

Understanding where these data are missing is, of course, just one piece of the larger conversation about how the structural features of our society have left some communities more vulnerable to the pandemic than others. If you’re interested, here is a great piece that delves into how inequity is playing a role as a “pre-existing condition” in our current healthcare system.